The Most Important

Memory

On eve of the Israelites’ emancipation from slavery in Egypt, God gives Moses and Aaron some final instructions regarding the grand escape. Every family shall sacrifice a lamb and put its blood on the doorposts and eat it hurriedly with sandals on and bags packed. But God’s instructions are not only an escape plan now. They are also instructions for eternity. God tells the Israelites, “Remember this day” (cf. Ex 12:14). “Mark it on your calendar. In fact, make it the beginning of your calendar, the first month of the year. Make it the founding event, the most important memory, go through its motions every single year” (cf. Ex 12:2). “Celebrate it ‘til the end of time” (cf. Ex 12:14).

Fast-forward over a thousand years from Moses to Jesus, and the Israelites are still remembering that Passover day. Jesus and his disciples go to Jerusalem to remember it. For them, Passover is not an idle memory, a pleasant recollection. It is a living memory, a memory that is true again and again. As the Israelites suffered in Egypt, so Jesus will suffer on the cross. As the Israelites were delivered, so Jesus will be resurrected. Over a thousand years later, it is still true. God is the liberator, the life-giver.

Today, three thousand years after Moses, the Jewish faith still celebrates the Passover. For them too, it is a living memory, a memory that they have lived over and over again. As their ancestors suffered in Egypt, they too have suffered: persecution in ancient Rome, organized massacres in Russia and Eastern Europe, the Holocaust. And as their ancestors found freedom from Egypt, they continue to find life too. How else would they have survived these atrocities? It is still true for them. God is the liberator, the life-giver.

In fact, if you consider that the Lord’s Supper is a Passover meal, we also celebrate the memory. We celebrate it every week—or perhaps even more often: “Whenever [we] eat this bread or drink this cup,” Paul says (1 Cor 11:26). Just as the Passover was originally ordained as the beginning of the calendar, the memory that would define time and life itself, so the Lord’s Supper begins our every week, reminding us that though the times may change, this memory will be true again and again: God is the liberator, the life-giver.

The Lord Still Dies

Every week, at the very end of the Lord’s Supper, we quote scripture: “For as often as [we] eat this bread and drink the cup, [we] proclaim the Lord’s death until he comes” (1 Cor 11:26). That conclusion has long puzzled me and left me feeling a bit empty. Why do we only remember the Lord’s death? Why not his resurrection? Why not new life?

Here’s my theory. It’s because the Lord still dies. It’s because there is still suffering in this world. There are still many Egypts, many Pharaohs, many chains in this world. We proclaim the Lord’s death not because we’re pessimists or doomsayers, but because we are rigorously honest and we are praying and hoping for more liberation, for a fuller resurrection. Our memory of Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection is not an idle recollection, a pleasant reminiscence. This memory is a defiant act of faith, a commitment to a different world—what Jesus called the kingdom of God.

Every week, we remember the Lord’s death so that we might be faithful to the work of the kingdom. When we hear about the folks who have lost their homes and their land to wildfires and floods, we remember the Lord’s death. When we hear about another school shooting, we remember the Lord’s death. When we hear about a community targeted with violence because of their difference—Asian, Jewish, Latino—we remember the Lord’s death. When we hear about another life lost to addiction, we remember the Lord’s death. When we hear about the utter poverty of factory workers and the dangerous conditions they daily endure, we remember the Lord’s death.

Johann Baptist Metz, a German theologian who has spent his life wrestling with the memory of the Holocaust, calls the memory of Christ “the dangerous memory of suffering.” It is a dangerous memory because it sees in the face of every suffering person the face of Christ, and it will not rest until they do. It is a dangerous memory because it defies the injustice of the world and commits to a different way, the way of Christ.

Not Just Back Then,

but Now

For the rest of the sermon, I would like to share with you some personal reflections. Here I am going to take a page from Paul’s book, and preface what follows with a reminder: “This is me speaking, not the Lord” (cf. 1 Cor 7:12; 2 Cor 11:17). So, take what rings true, and leave the rest. (That goes for all my sermons, of course.)

When the Israelites celebrate the Passover or when we celebrate the Last Supper, what we’re really celebrating is not an event shrouded in the mists of history. What we’re really celebrating is a God who liberates, who gives life. Not just back then but now. What we’re proclaiming is that as sure as the week has seven days, or the year 365, suffering and oppression do not have the last word. God is always present, always redeeming.

If that’s true, then where are the liberation stories of recent generations? There’s one in particular that is meaningful to me as a native of Richmond, and I would like to share it with you today. April 3, 1865, is often cited as the day that Richmond fell, and with it the Confederate States of America. That is certainly how I was taught to remember the day. But as I read through the story of that day now, I cannot help but hear echoes of an older memory.

One woman living in Richmond at the time remembers that day as a day of darkness: “We covered our faces and cried aloud,” she writes. “All through the house was the sound of sobbing. It was the house of mourning, the house of death.”[1] Such words could easily have been written of the Egyptian houses on that dark night of the Passover (cf. Ex 12:30).

But Reverend Garland H. White, a former slave who was serving as a chaplain in the Union Army, describes a very different scene: “A vast multitude assembled on Broad Street, and I…proclaimed for the first time in that city freedom to all mankind. After which the doors of all the slave pens were thrown open, and thousands came out shouting and praising God.”[2] Another chaplain writes also of divine deliverance, “We brought…heaven-born liberty. The slaves seemed to think that the day of jubilee had fully come. How they danced, shouted…shook our hands…laughed all over, and thanked God…!”[3] And then in a passage that recalls the divine command to remember the Passover forever (12:14), he writes, “It is a day never to be forgotten by us till days shall be no more.”[4]

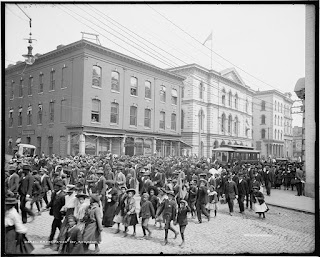

Indeed, forty years later, on April 3, 1905, Richmond hosted the Emancipation Day Parade, commemorating the day that many slaves in Richmond and across the south were actually liberated. Thousands gathered for the festivities and celebrated with a procession through the city streets that ended up at the Broad Street Baseball Park. (If there are any history buffs among you, I’d be curious to learn where that was exactly.)

Emancipation Day Parade, Richmond, Virginia, April 3, 1905[5]

A Passover in Richmond

As a native of Richmond, I was taught to remember April 3,

1865, as the fall of this city and the fall of the Confederacy. But as a

follower of Christ, I am invited to remember the God who liberates, who gives

life. Which means I am invited to remember April 3, 1865, as a day of divine

deliverance, a holy Passover. A heavy day and a day of great cost, yes, as it seems

to have been for Egypt thousands of years ago, but a day when the God the

liberator, God the life-giver, passed over the city—this city!—bringing freedom

to thousands.

I am honored to call Richmond home, if for no other reason than that here happened a Passover. And this memory, which is but one of many in the long line of memories going all the way back to Egypt, a host of memories which ring most loud and most true in the Last Supper of Christ—this memory is for me a defiant act of faith, a commitment to a different world. It means remembering the Lord’s death in the subjugation and suffering of those today who still share the struggles that those slaves did: educational barriers, labor inequalities, presumptions of guilt and dangerousness—and perhaps more than anything else, the unjust inheritance of shame. This memory means believing that God the liberator and life-giver is against that suffering still, that Jesus Christ is in that suffering still, and that his love will raise new life from a history of hurt. It means that while many dismiss or minimalize the suffering of others, I remember the death of my Lord, who is still dying in so many places. I try hard to see the face of Christ in the anger, the sadness, the resignation of others, and I defiantly trust that this is not how the story ends. Not for the Israelites. Not for Jesus. In God’s calendar, this is just the beginning.

Prayer

Whose death is a dangerous memory

That protests the suffering of the world

…

May the memories

Of Passover and the Table and April 3

Inspire us to celebrate

The God who liberates and gives life,

And to share in God’s liberation

By living in the way of your love,

Which is stronger than death.

Amen.

[1]

A Virginia Girl in the Civil War (ed.

Myrta Lockett Avery; New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1903), 362.

[2]

A Grand Army of Black Men: Letters from

African-American Soldiers in the Union Army, 1861-1865 (ed. Edwin S.

Redkey; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 175-176.

[3]

The Military and Civil History of

Connecticut during the War of 1861-65 (eds. W. A. Croffut and John M.

Morris; New York: Ledyard Bill, 1868), 791. These are the words of Henry Swift

DeForest.

[4]

The Military and Civil History of

Connecticut, 792.

[5] James Branch Cabell Library, Special Collections and Archives.

No comments:

Post a Comment